I first discovered Claudio Rocchi through my father’s vinyl collection, which featured his Il Volo Magico N. 1 LP as one of his most prized possession. As a small-town hippy and prog enthusiast teenager in the early 70s, my father was enthralled by Rocchi’s Eastern-tinged esoteric folk; as a small-town goth teenager in the early 2000s, I was way less impressed by Rocchi’s cheesy singing in his hit song La Realtà Non Esiste [Reality doesn’t exist]: “Quando stai mangiando una mela / tu e la mela siete parte di Dio” [When you are eating an apple / you and the apple are part of God].

Well, I was very wrong.

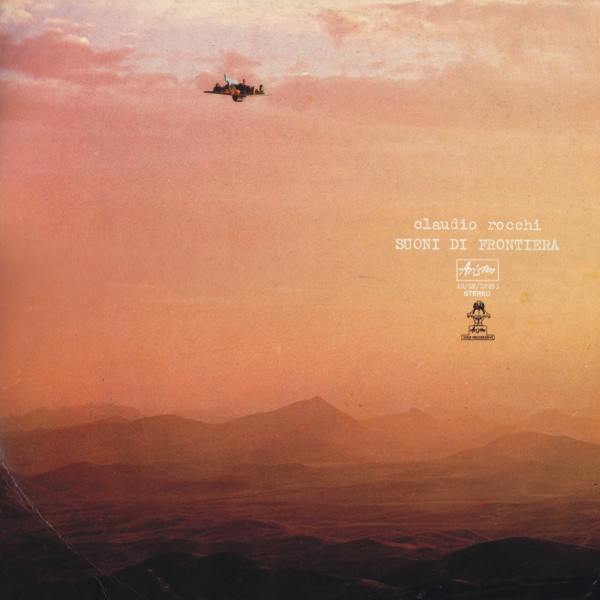

Twenty-odd years later, I am still on the fence about Rocchi’s psychedelic folk – mainly because of his singing, which still feels very over the top. His Suoni di Frontiera [Frontier Sounds], however, has become one of my favourite experimental records of all time, and now I can even understand Rocchi’s appeal as a cult figure for the Italian post-1968 generation.

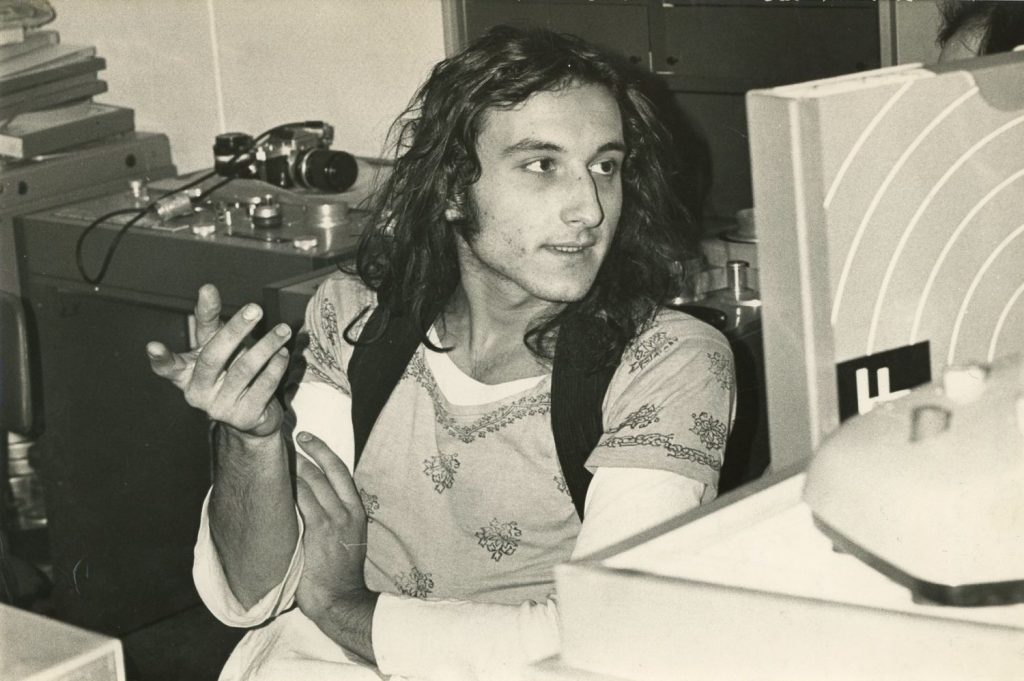

Claudio started his music career in 1969 in the Milanese prog-rock outfit Stormy Six and soon after went solo with his first LP Viaggio [Journey] (1970) and the aforementioned Volo Magico N.1 [The Magic Flight N. 1] (1971), which became an instant classic.

In a time of social unrest and student activism, when political engagement was compulsory in the counterculture, Rocchi focused on the spiritual, singing a universal message of love and self-discovery that has stood the test of time better than most of his more politicised contemporaries. After many trips to India and Nepal, at the height of his career the musician took his vows and became a Hare Krishna monk: “if you really want to understand a philosophy, it’s not enough to read about it: you need to live it”.

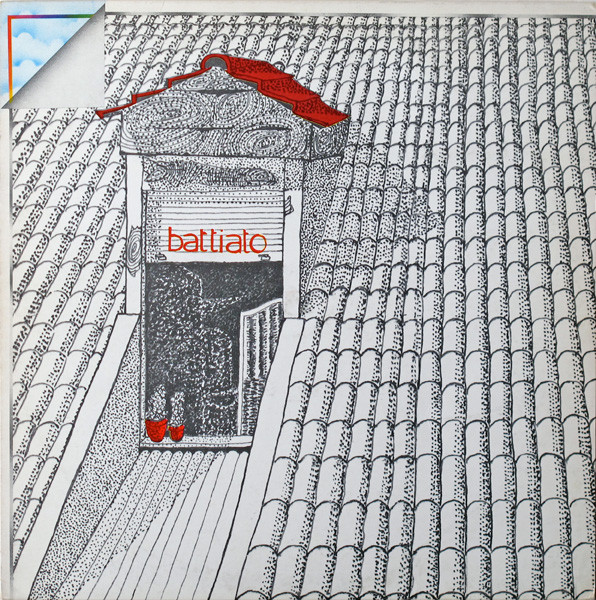

Before leaving his mundane life behind, Claudio abandoned folk as well and began experimenting with new sounds, first in the eponymous Rocchi (1975) and finally in Suoni di Frontiera (1976). Recorded at Rocchi’s home studio in Milan, the LP features seventeen sonic fragments of electrically charged psychedelia, made of samples, chipped melodies, distorted voices and ethnic inspirations. The musician himself describes his compositional process in the linear notes penned for the 2009 reissue on Die Schachtel:

The research documented here refers to the period 1974-1976. I stepped out of the song-form of my early works and I entered the faithful experience of a liberating sound, which surely anticipated the experience of the mantras of a following phase of my life (fifteen years as a Bhakti monk). The instruments are those of the time: VCS3, keyboards, 1/4 inches tapes, Revox, Binson echoes, sounds of life, magnetic cut and paste long before digital post-production.

Inspired by electroacoustic music and his travels to faraway lands, Suoni di frontiera sounds incredibly alive and is no less emotional than his folk records, especially in its more melodic moments, such as the lysergic ‘Il Risveglio’ [The Awakening], the nostalgic ‘HO’ or the kosmische ‘Il Rame e gli Armonici’ [Copper and Harmonic].

From the intimacy of his home studio, Rocchi explores different sonic landscapes: in ‘Per antichi canali’ [Through Ancient Channels] loops become electric mantras, the bells of ‘Dopo Arona’ [After Arona, a town north of Milan] evoke a Middle Eastern vibe and the upbeat rhythm of the southern Italian folk dance Tarantella is deconstructed in the syncopated track of the same name.

There’s an urgency and a sense of playfulness that runs through Suoni di frontiera and makes for a very joyful listen. You can sense that Rocchi is experimenting with sound as a means of self discovery, which becomes most apparent in his use of natural body rhythms in ‘Ritmi’ [Rhythms] and ‘Suoni Interni’ [Internal Sounds] – the latter based on the sound of his son’s heartbeat, recorded by the “BCF Echo Sounder ultrasonic detector of Manuela [Claudio’s wife] in the fourth month of conception of our son Tioca”.

In the original liner notes, the musician elaborates on his view of the rhythmic essence of human life:

The rhythm of the heartbeat of a baby who is about to be born leaves no doubt about the speed and direction of the vital force. How the rhythm of breathing is closely connected with existence itself is clear to every man. These are the two main and steady rhythms of every physical experience with music.

Rocchi believes in the sacredness of music and, on a more worldly level, in its power to bring people together, as attested by his yearlong commitment as radio host, first in Italy in the 70s and then with his own ‘Himalayan Broadcasting Company’ in Katmandu in the 90s. His faith in the healing and transcendent quality of music informs the whole Suoni di Frontiera: it’s a wonderful record – or experience, as the musician would say – where sound is energy, frequency and life force, able to break barriers and expand horizons.

In hindsight, my teenage wariness of Claudio Rocchi’s alleged cheesiness might have been symptomatic of the greater condition of our post-post-modernist time – that is, our reluctance to take seriously art that engages with moral values or existentialist questions.

David Foster Wallace summarised the issue brilliantly in his essay about the actuality of Dostoevsky:

It’s actually not true that our culture is nihilistic for there are certain tendencies we believe are bad. Among these are sentimentality, naiveté, archaism, fanaticism. It would probably be better to call our own art’s culture now one of congenital skepticism. We believe that ideology is now the province of rival Special Interest Groups and Political Action Committee all trying to get their slice of the big green pie… and, looking around us, we see that indeed it is so. But if this is so, it’s at least partly because we have abandoned the field.

Claudio Rocchi hadn’t abandoned the field yet. And if he sounds naive to our post-millennial ears, that says more about our cultural situation than about his artistic intentions.