In a wake-up call to his fellow downtown musicians published in EAR Magazine in 1978, No Wave composer Rhys Chatham weighed in on the state of what he dubbed post ‘60s traditionalist music:

In the past 10 years or so we’ve had minimal music, meditation music, hypnotic music, phase music, down-home music and other exciting new forms. Exciting that is when they first came out. What’s happening to us, though? Instead of thinking of new things to do, it seems as if a new tradition is being created. It’s SAFE to write minimal music, process music, meditational / quasi religious music in 1978! The great thing about the USA is that we have no culture to speak of, we’re not bound and chained by a tradition and an architecture which date back to 1400 AD. We’re perfectly set up to look forward. It’s a commodity we should take advantage of!

While this might have been true for the New York avant-garde, in Italy the cultural landscape was quite different: bound and chained by a tradition dating back to 1400 AD — or even as far as 600 BC, if one counts the Roman Empire – Italian minimalists still sounded fresh and compelling in the late 70s. Besides, one could also argue that ‘60s minimalism, unlike much of the 20th-century avant-garde, was also deeply aware of the past in embracing tonality and consonance. Italian minimalism may not have been groundbreaking, but it offered an original interpretation of the ‘post ’60’ American tradition that Chatham so vehemently rejected. It wasn’t a unified movement, but a constellation of artists with eclectic backgrounds – spanning prog rock, experimental theatre and classical music – who produced minimalist works during the latter half of the 1970s.

Between 1977 and 1979, prog rocker turned avant-garde maverick Franco Battiato and his frequent collaborators Francesco Messina and Giusto Pio composed a small canon of minimalist piano works focused on resonance. These pieces sought to explore the very essence of sound through the reverberation of the piano’s keys, inspired by key aspects of minimalism such as drones, loops and the influence of non-Western music. To paraphrase Steve Reich, the composers were looking East, to Indian music and the spiritual teachings of Armenian mystic Gurdjieff, to write “Western music with an Eastern approach“.

Francesco Messina – Untitled

The most accessible piece of the lot is the blissful ‘Untitled’ by Francesco Messina (b.1951). Originally recorded in 1979, it was only released in 2013 as a bonus track on the Die Schachtel CD edition of Messina and Lovisoni’s cult LP Prati Bagnati del Monte Analogo. Light in the Attic included the piece on the compilation The Microcosm: Visionary Music of Continental Europe in 2016, and Superior Viaduct reissued it in Messina’s EP Reflex in 2022.

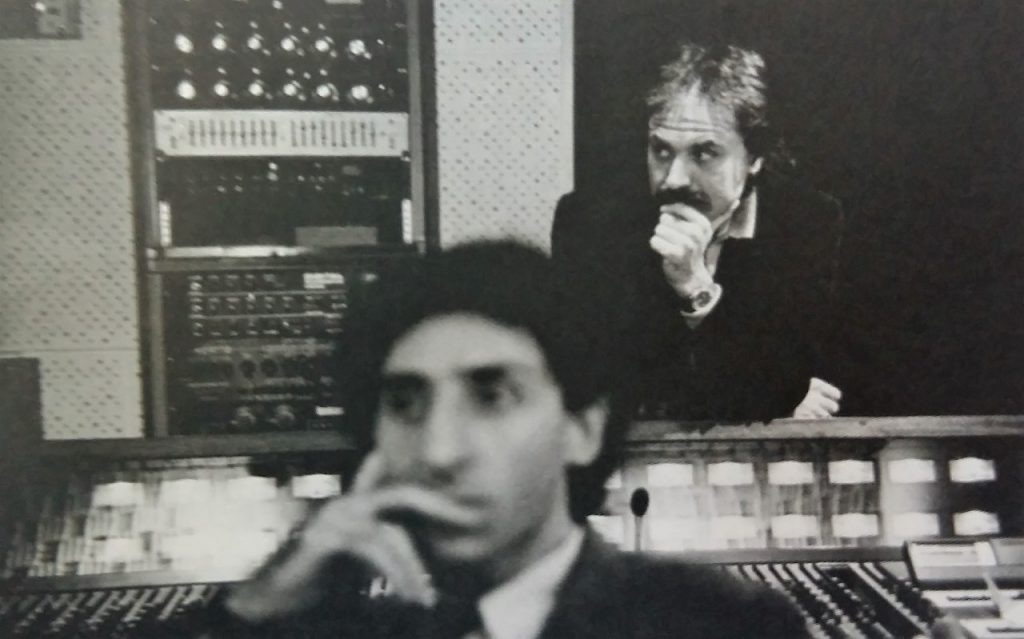

Messina began his partnership with Battiato in the early 70s, doubling as his go-to graphic designer and “apprentice musician”: he was playing keyboards in his touring band and occasionally guested as studio producer for some of the artists Franco was working with. Battiato was a huge influence on the young composer and played a key role in the release of his first album, the aforementioned split LP Prati Bagnati del Monte Analogo.

A second crucial encounter was a series of concerts organised by the Venice Biennale in 1976 to showcase American minimalist music, which was gaining widespread acclaim in the cultural mainstream. Messina attended performances by Steve Reich, Charlemagne Palestine and Terry Riley, as well as a staging of Einstein on the Beach by Robert Wilson and Philip Glass — an experience he later described as “a revelation”. In fact, that same year he started composing the material that would lay the groundwork for his piano works. As detailed in the linear notes of The Microcosm: Visionary Music of Continental Europe: “I was maniacally interested in the harmonics that each instrument generated as a consequence of reiterated repetitions and equivalent microvariations”.

‘Untitled’ is built upon a single arpeggio, played repeatedly with little variations in intensity, tempo and pitch. The final note of every chord is sustained, creating a cascade of harmonics that expands as a subtle background, accompanied by Lovisoni’s gently reverberated flute. It’s a simple, but beautiful piece, its atmosphere bucolic and serene. It could be described as the musical equivalent of a Palladian villa — its classicism and elegance emerging from a certain austerity and from the rigorous symmetry of its straight lines.

Messina has openly acknowledged his debt to Steve Reich, although his style is less energetic than that of the American composer. His greatest inspiration was still his mentor Battiato: in those same years, the Italian musician was also exploring overtones of sustained piano notes in his L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie.

Franco Battiato – L’Egitto prima delle sabbie

I consider this period, which includes L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie, to be the highest point of my production. I was able to make music that was essential and of a certain purity. The results were also determined by the instrument itself: the piano with its world of resonances. It is a micro-polyphonic language, full of ‘beats’ and ‘sympathetic sounds’. These resonances are still, in my opinion, the ideal form to express a certain world. This is my ideal soundscape.

Franco Battiato,Tecnica Mista su Tappeto.

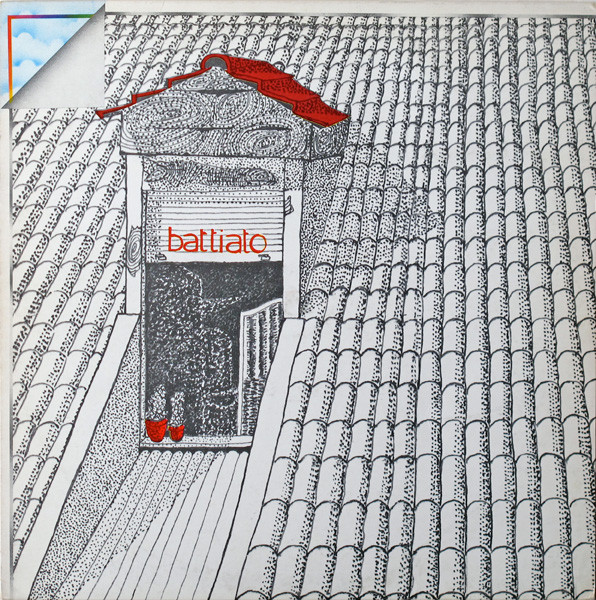

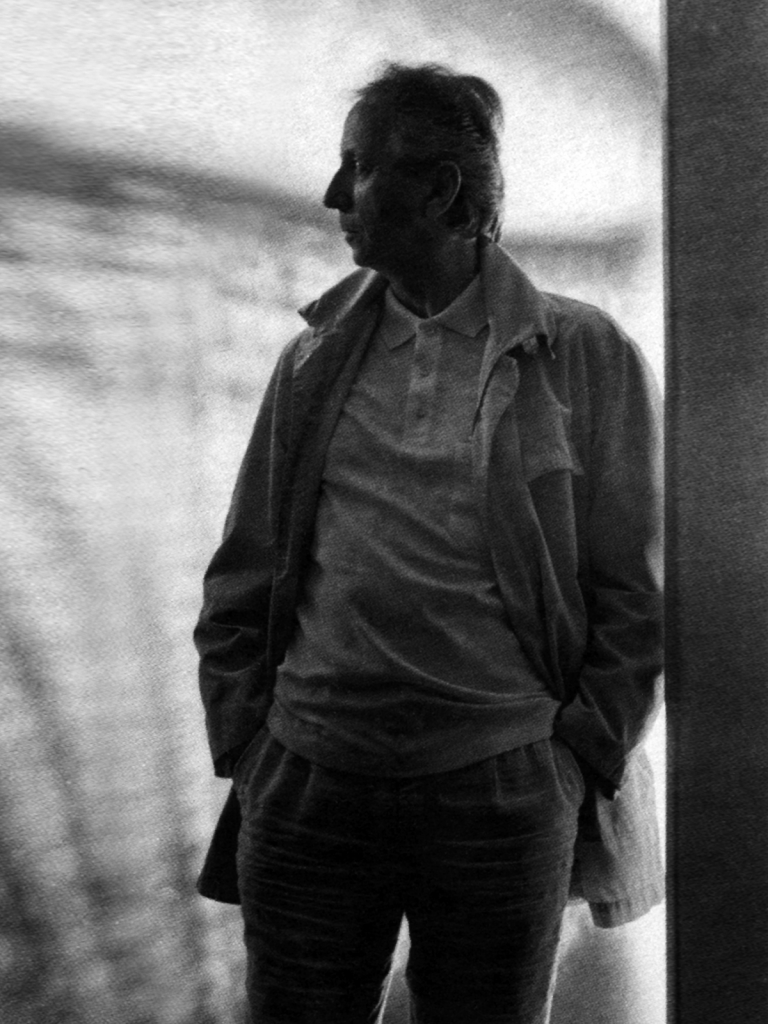

In 1978, when L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie [The Pre-sand Egypt] LP came out, Franco Battiato (1945-2021) was a former prog-rocker in existential crisis who had left pop music behind to explore new sound frontiers, first with the electronics of Sulle Corde di Aries (1975) and Clic (1974), then with the radio collages and organ improvisations in M.elle Le “Gladiator” (1975) and finally with the idiosyncratic modern classical of Franco Battiato (1977) and Juxe-Box (1978).

The piano piece ‘L’Egitto prima delle Sabbie’ builds upon the research into overtones the musician begun a year earlier in ‘Zâ’, featured on the Franco Battiato LP. Both compositions focus on the harmonics produced by the hammer’s stroke on the piano strings, albeit in slightly different ways: ‘Za’ consists of a vigorously repeated single chord, while ‘L’Egitto prima delle Sabbie’ is a looping arpeggio, its vibrations enhanced by the sustaining pedal.

Battiato is using repetition to achieve a sort of stasis, ruptured by the reiterated note(s)’s minimal variations. However, the repeated pattern is only instrumental to the true essence of the pieces, the micro-melodies hidden behind the notes and brought to the fore by their resonance. This process, in some respects, mirrors La Monte Young’s use of sustained drones, which reveal and amplify the overtone series inherent in each pitch. But if Young emphasises extreme volume and continuous duration in his quest for ‘eternal music’, Battiato takes a more subdued approach, creating music that aspires to become silence.

In a 1978 interview, the Italian musician described ‘L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie’ and its exploration of the minimum threshold of audibility as “music that hides silence behind it”. Battiato considers silence both as an expression of a spiritual dimension and as a way to connect to it in contemplation: “L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie helped me meditating. When it was over, I had the feeling that the room would fill itself with a certain sonic purity”. Accordingly, inviting the listener to become aware of the barely audible becomes an invitation to experience the world anew. Far from being mere investigations into the physiological characteristics of sound, ‘Zâ’ and ‘L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie’ are grounded in the notion of sound as a sacred vibration that connects one to oneself and to a higher state of consciousness.

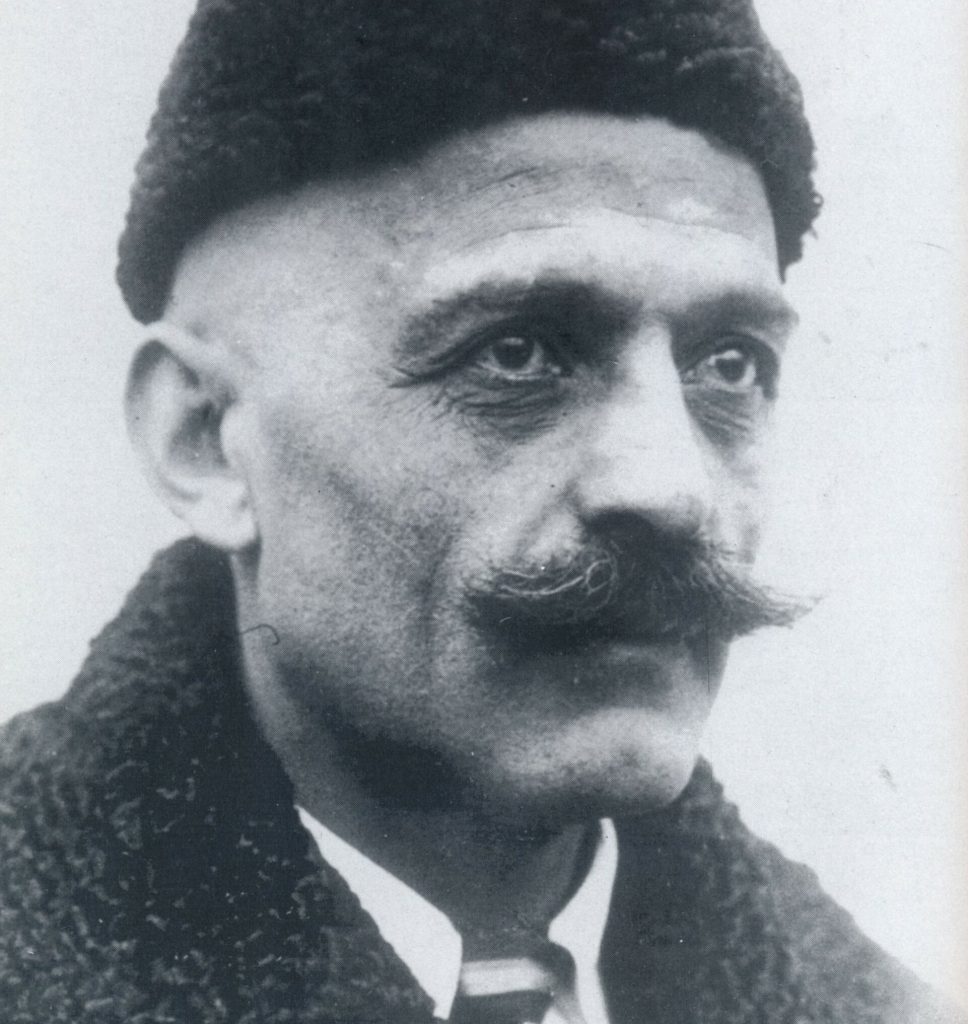

It is no coincidence that, around the same years, Battiato encountered the spiritual teachings of the Armenian mystic Gurdjieff. The title L’Egitto prima delle Sabbie alludes to Gurdjieff’s book Meetings with Remarkable Men, in which he claimed to have found a map of the pre-sand Egypt—evidence, he suggested, of an ancient civilisation possessing superior wisdom and a profound relation to the cosmos.

It’s no coincidence that, around the same years, Battiato encountered the spiritual teachings of the Armenian mystic Gurdjieff. The title L’Egitto prima delle Sabbie alludes to his book Meetings with Remarkable Men, in which Gurdjieff claimed to have found a map of the pre-sand Egypt — evidence, he suggested, of an ancient civilisation possessing superior wisdom and a profound relation to the cosmos.

The son of an Ashug, a representative of the centuries-old tradition of Armenian bards, Gurdijeff considered the musical scale as a model of the universe, regarding sound to be the sacred vibration of reality. Although Battiato never mentioned this in relation to his own piano works, the mystic believed that perceiving the inner octaves of a composition was akin to understanding the structure of reality — a belief which somehow parallels the musician’s research on resonance as a way to connect with the world in a deeper way.

Granted, ‘L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie’ is not easy-listening music and it takes a while to warm up to it. It took me a while to “get into it” and it was only after many listens that I could truly enjoy it, when I was finally able to fade out the notes in the foreground and concentrate on the micro-melodies that animate the background.

There’s no need to ascribe spiritual meaning to the music to appreciate its purity; it’s an exercise on awareness, or deep listening if you will, which requires only a little patience and openness. This idea of sonic meditation would be taken further by Giusto Pio on his Motore Immobile LP, a work born out of his improvisation sessions with Battiato as they explored the overtones of violin and voice.

Giusto Pio – Ananta

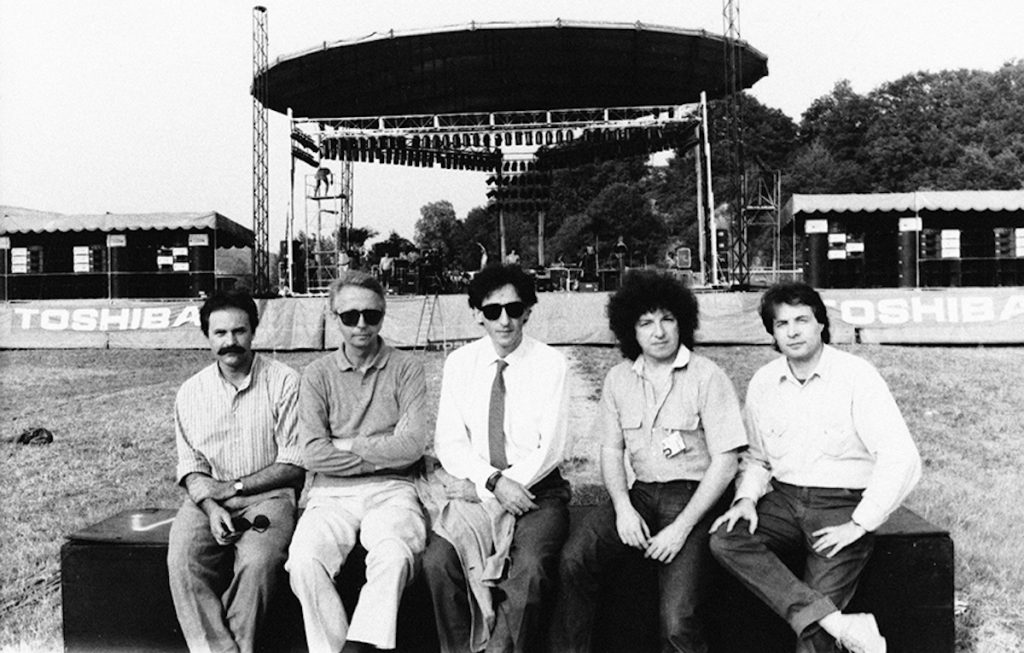

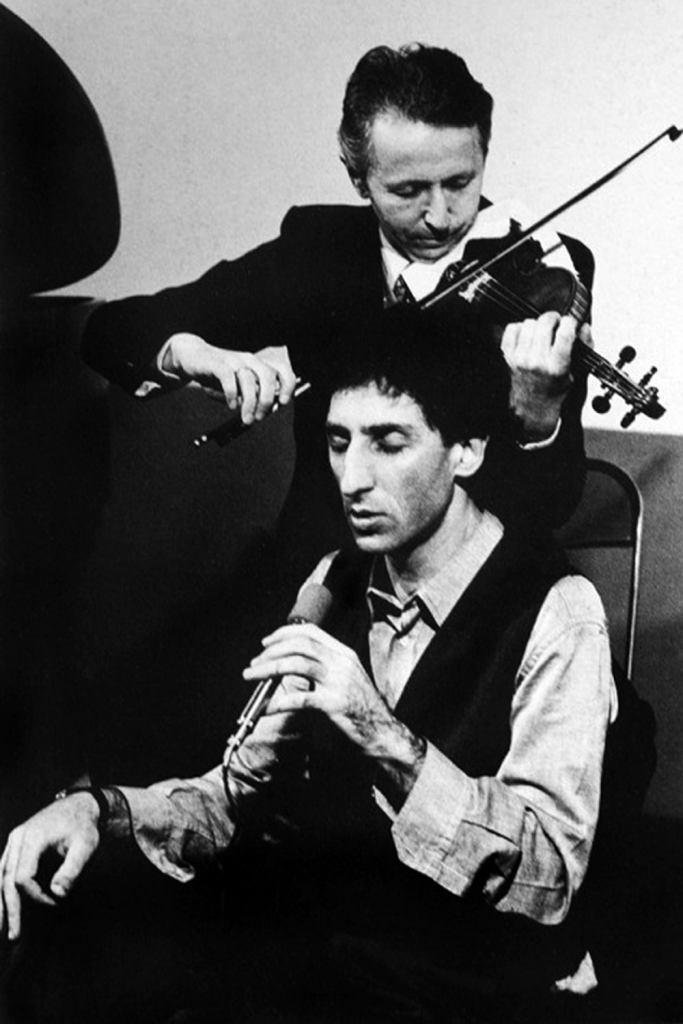

Violinist & composer Giusto Pio (1926-2017) was instrumental in acquainting Franco Battiato with classical music, and by 1977 the two were inseparable friends and collaborators. Battiato had no formal training and only began studying music theory in his 30s, after Stockhausen famously urged him to do so around 1973. Looking for violin lessons to deepen his understanding of the instrument, he was recommended to Giusto Pio, the first violinist of the RAI National Symphony Orchestra.

The two bonded over a shared hatred of the rigid dogmatism of serialism, the mainstream avant-garde of the time, embarking on a 20-year artistic partnership that would see Pio co-author and arrange Battiato’s most successful pop album. Their early efforts, however, were decidedly experimental: the years between 1977-79 were the pinnacle of Battiato’s engagement with his own form of classical contemporary and in 1978 Pio released his first album, Motore Immobile [The Prime Mover], produced by Franco for the famed avant-garde label Cramps.

In his recently published book Battiato & Pio. Uno Sguardo Dal Ponte [A Look From the Bridge], Pio’s son Stefano details the duo’s early improvisations:

Battiato sang sitting on the floor, legs crossed, while Pio played standing in front of him, his violin very close to Franco’s head. This was the most immediate way for him to perceive the overtones emanating from the violin’s body. The love and search for ‘pure’ sound (not bound to a ‘language’ and its syntax), which refers to the meditative dimension of the mantra, developed precisely during those improvisations, which were extremely important for both Franco’s and my father’s artistic development.

As Giusto Pio himself pointed out, Motore Immobile was born from this “search for pure sound”: “I chose, or rather, this music chose me, when I understood the difference between sound and language”. The LP’s B-side track, ‘Ananta’, borrows the piano chords of ‘L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie’ and grounds them over a continuous drone played by the organ. The harmonics resonate against the organ’s seemingly motionless backdrop, a vertical force ascending over the horizontal, sustained tone. Lonely scales are scattered throughout the piece, adding a slight variation to the recurring pattern. As in Battiato’s piece, it’s music that strives to become silence, for time to come to a standstill.

Ananta is a Sanskrit term that roughly translates as “endlessness”. It’s associated with Om, the infinite symbol in Hinduism and the universe’s primordial sound. Pio explained:

Both ‘Ananta’ and ‘Rappel’ [title of another composition, ed.] are terms and concepts used in the teachings of the Greek-Armenian mystic Gurdjieff, as well as in the courses of his pupil Henry Thomasson, which Franco and I attended at the time. These teachings were based on the Fourth Way, on exercises in self-awareness and the search for one’s true self. In my intention, the uniform sound [of Motore Immobile], continuous until its dissolution in silence, prepared and induced recollection, introspection and the search for transcendent realities.

‘Ananta’ could be inscribed in the tradition of spiritual minimalism, albeit its warmth distinguishes it markedly from Pärt and Gorecki. The serenity of the piece also sets it apart from its American counterparts: while Young’s suspended tones are furiously Dionysian, Pio’s are decidedly Apollonian. Echoing French musicologist Jankélévitch’s dialectic of music and stillness, one could say that silence is at the heart of Pio’s compositions: “Silence is the desert where music blooms, and music, the flower of the desert, is itself a kind of mysterious silence”.

beyond Minimalism

If in 1978 Rhys Chatham was “perfectly set up” to look beyond the tired American minimalism, Battiato, Pio and Messina reached their creative peak in their reinterpretation of it. It was only the following year, in 1979, that the Italian musicians confronted the limits of their endeavours – perhaps it had indeed become SAFE to write minimalist music.

The rigorous research into harmonic resonances that Battiato began with ‘Zâ’ and ‘L’Egitto Prima delle Sabbie’ was a point of no return. After his impossible quest for the essence of sound, only two options remained: the silence of the enlightened or the way back to a more accessible form of music.

Battiato chose the second path, releasing his first pop album in 1979, as did Messina and Pio, who followed il Maestro in integrating experimental idioms into traditional song structures. Somehow, the trajectories of American and Italian post-minimalist music run parallel: if the New York downtown scene incorporated minimalism into an avant-garde form of rock’n’roll, Battiato and Pio created a highly personal blend of pop, classical and experimental music. As a testament to this change, the pair recycled the arpeggio from ‘Untitled’ to write the Kraut-inspired Il vento caldo dell’estate [The Warm Wind of Summer] for Italian pop star Alice. The song went on to top the charts in 1981, and during the studio sessions, Alice met Francesco Messina, who would later become her husband. The journey had come full circle.