Franco Battiato is a balera singer turned avant-garde composer, and that’s precisely where the strength of his music lies. The Italian term balera doesn’t have a perfect equivalent in English: think of an unpretentious, all-ages working-class dance-hall, where people would swing to the traditional ballroom styles of “liscio” (waltz, polka, mazurka) and to modern pop hits.

The balera was the starting point for Battiato, who moved from his native Sicily to Milan in the 60s to pursue a musical career. For about ten years, he played covers all night long for a crowd that just wanted to dance, singing and occasionally doubling on guitar. It was a tough apprenticeship, yet invaluable in developing a deep-rooted instinct for melody. As he reminisced in his conversation book with the musicologist Franco Pulcini, Tecnica Mista su Tappeto [Mixed Media on Carpet]:

When I was eighteen or nineteen, I began the classic apprenticeship at the balera. It was a great school, with a fierce audience that just wanted to have fun and dance. If you weren’t good enough, they would boo you. Those were tough times. You had to sing songs you didn’t like, such as certain hit parade songs. The balera was a great school of discipline! I’m glad I did it, even if I could have managed a few years less… It lasted from the age of eighteen to twenty-four. I remember doing everything during that period: I played at birthday parties, New Year’s Eve celebrations…

The balera years, with their endless performances of traditional Italian canzoni and emergent rock hits, instilled in the musician a distinctive gift for harmony, which would reach its full expression in his later pop chapter. And even during his experimental phase, a certain quest for beauty, a notion very frowned upon by the avant-garde, found its way through the most adventurous layers of his music. This is as true of his electro-acoustic production as it is of his forays into modern composition, which I want to focus on here.

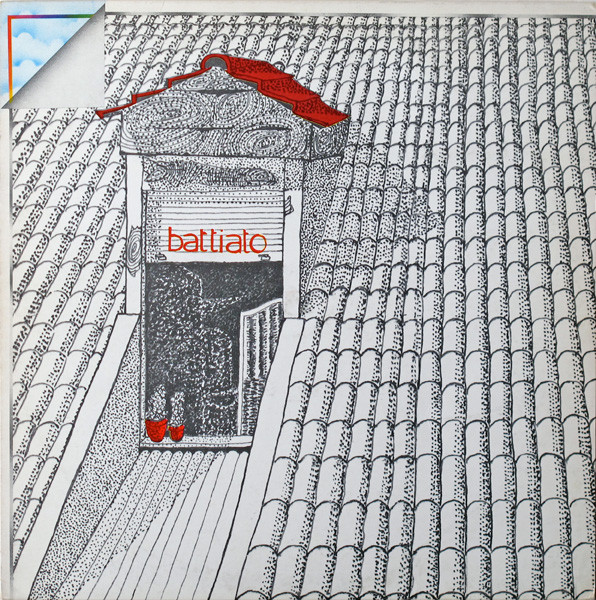

Battiato went classical in 1977, after exploring prog rock and electronics in a string of albums released between 1972 and 1976. With his Battiato LP, he abandoned magnetic tapes and synthesisers for purely acoustic instrumentation, embracing the written score instead of long improvisation sessions on his faithful VCS 3. The result is a highly personal form of classical contemporary, far removed both from the institutional avant‑garde of the time, dominated by serialism and indeterminacy, and from his earlier minimalist influences. Franco adopted some tropes of this language to carve his own path and express his evolving interests: for him, an artist who has always been open to trying new things, modern composition becomes a new colour in his musical palette.

Battiato was well aware of, and at times dismissive toward, new music until the high priest of Neue Musik himself, Karlheinz Stockhausen, encouraged him to study music theory.

In 1972 Stockhausen came to Milan to give a concert. I went to see him and gave him a copy of my Pollution LP [Battiato was introduced by his producer Luigi Mantovani, who was working for Island Records at the time, ed.]. As always happens with fathers, his children were fans, so he was forced to listen more closely. In 1975, he contacted me about a role in one of his operas, Inori, so I travelled to Germany and stayed at his house in Kürten for a week. At one point he brought out this huge, rectangular score that was more than a metre wide. He handed it to me and said: “This is your part”. But I replied: “I can’t read music”. It took him a few minutes to understand. I kept repeating: “I can’t read music; I don’t know traditional notation”. Eventually he closed the score and said: “ein Moment”. And he devoted me the whole evening, hours! with a typical German determination. He inspired me so much that as soon as I got home, I began teaching myself theory and solfeggio, and later studied harmony and composition with the great Maestro Dionisi.

Stockhausen gave the initial spark to his new fire, but as decisive as this encounter was, Battiato owed his musical development also and above all to the musicians he was spending time with in Milan. The city in the 1970s was in full cultural ferment and his flat became a regular destination for many students of the conservatory: “I had many friends, including some exceptional pianists”.

One of them was Antonio Ballista, whom Franco asked to collaborate on his Battiato LP. An accomplished pianist, Ballista played a key role in introducing new music in Italy, both as a soloist and in his piano duo with Bruno Canino, which has been performing since 1953. Eclectic and open-minded, he wasn’t limiting himself to the classical tradition, but ventured into ragtime, rock, and film music. His contribution to Battiato was essential as he helped Franco, who was a relatively inexperienced music student, to develop his ideas and write them down on the pentagram. He also designed the album cover, a beautiful, minimalist lithography of a loft which represents perfectly the airiness of the music.

The record features two side-long pieces, each a world in itself: ‘Zâ’, more abstract and hermetic, and ‘Cafè-Table-Musik’, more dreamy and expansive.

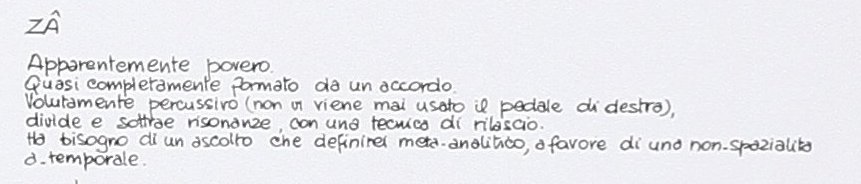

‘Zâ’ consists of an insistently repeated piano chord, with slight variations, bringing the microtones of the notes to the fore. This piece marks the beginning of Battiato’s research into overtones, which I have written about extensively here. Probably inspired by his early experiments with the prepared piano in the style of John Cage, Franco tried out his own percussive “preparation” by using the piano’s pedal. On the back cover, he described the piece as “apparently poor, almost entirely composed of a single chord. Deliberately percussive (the right pedal is never used), it divides and subtracts resonances through a release technique [of the pedal].”

The title is a typical example of his subtle sense of humour: Zâ is a made-up word from the fictitious poem I deliri [Deliria], invented by record executive Luigi Mantovani to promote the LP. Mantovani himself recounted the episode in Zuffanti’s book Battiato. La voce del padrone. 1945-1968: nascita, ascesa e consacrazione del fenomeno [Battiato. His Master’s Voice. 1945–1968: Birth, Rise and Consolidation of the Phenomenon]:

When the record came out, as part of a marketing campaign of the “there’s no money” variety, we decided to tickle the curiosity of the musical intelligentsia of the time. We invented the story that one of my lost and unknown writings had provided Franco with the inspiration for ‘Zâ’. As indisputable proof, we printed a postcard reproducing a short extract from that work, I Deliri.

…and then one day the people said: enough!

Enough of Manichaean situationisms, enough of post‑Weberian and pre‑Cagean sociological nemeses. Give them back the music and claim the sound for yourselves!

The people laughed with joy and cried: Zâ!”

Playful approach to marketing aside, ‘Zâ’ is by no means easy-listening music. The minimalism of its structure and the purity of its sound make for a meditative experience, but that’s not quite the balera instinct I was referring to. This instead comes to the fore in ‘Cafè-Table-Musik’, one of Battiato’s most beautiful composition. An “orphic collage full of wrong citations”, the piece presents a series of spoken-word and sung sketches interspersed with three piano interludes. Even its title is a “wrong quote”, a nod to Proust who supposedly referred to his own books as “coffee table books”.

Ballista doubles on voice and piano, joined by soprano Alide Maria Salvetta, a leading figure in contemporary music and his frequent duo partner. Battiato had already experimented with (tape) collage in Clic and M.lle Le Gladiator, but here his ambition reaches a new scale: the composition is a stream of consciousness, recorded ex novo in studio, which weaves together extracts of La Chanson de Roland, misquoted poems, echoes of his native Sicily, and everyday phrases. As he wrote in the liner notes, “there is a reality represented within an imaginary theatre”.

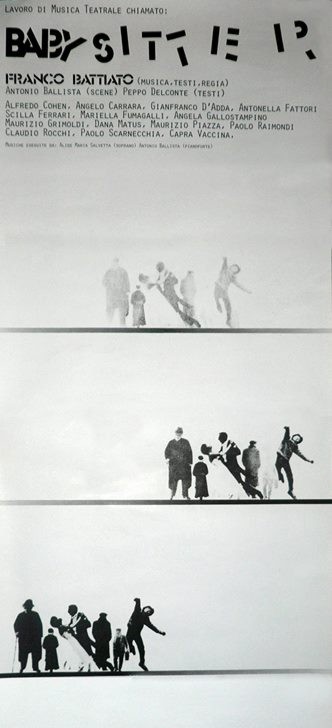

In fact, the spoken‑word passages and piano arpeggios were first conceived for a very real stage production: Baby Sitter, a theatre piece Battiato devised and directed in 1977. After attending Einstein on the Beach by Wilson & Glass at the 1976 Venice Biennale, he was inspired to create a play of his own. Maurizio Piazza, the production’s lead actor, describe it as “a series of tableaux vivants with music: it was a theatrical performance which had a very beautiful sonic poetics.”

Only a handful of photos documenting the piece have survived; however, in terms of the music borrowed in ‘Cafè-Table-Musik’, this couldn’t be more different from Philip Glass. Gone is the hectic repetition of pattern, replaced by a very serene, almost bucolic, sound environment. Battiato seems to paint an imaginary landscape, repurposing fragments of European literature to create a metaphysical locus amoenus.

This multi-layered mosaic of text excerpts echoes another masterpiece of postwar avant-garde, the groundbreaking Sinfonia (1968) by Luciano Berio. I may have been influenced by a very emotional performance of the work by the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia that I witnessed recently in Berlin, but the first thing I thought as the London Voices came in on cue is that their spoken-word bits were very Battiato-esque.

Sinfonia unfolds as a sonic collage of literary and everyday sources, moving between excerpts from Lévi‑Strauss, Joyce and Beckett to tape‑recorded conversations. The juxtaposition of voices and languages in Battiato’s collages, as well as their “varying degree of textual intelligibility”1, feels somehow indebted to it. The two musicians even knew each other, although Battiato ungenerously considered Berio “a bureaucrat of the avant-garde”2, while the latter simply ignored him.

Of course, their music and their attitude were worlds apart. In 1977 Berio was an established composer who had reshaped post-war serialism, while Battiato was an outsider with a limited knowledge of music theory, composing entirely by intuition and relying on Ballista (and later by his violinist and co-writer Giusto Pio) to bring his ideas to full form. This intuition, honed by his balera years, seems to respond to a very deep-seated need for harmony, which emerges beautifully in the piano interludes of ‘Cafè-Table-Musik’:

I believe in a “Pythagorean” music, which I feel instinctively. It’s as if I were constantly consulting the needle of perfection that lies within each of us, as Socrates did with the Oracle of Delphi. I have a precise perception of the music that is right for me. I seek it out and avoid the music that is wrong for me. Sound travels through space. It’s a wave that reaches me.

The three interludes, each based on a simple arpeggio, sound indeed as Pythagorean music of the sphere. They all have a very “pure”, soothing quality to them: one might say healing, without the New Age connotation of it,

but rather shaped by a classical aesthetic that identifies beauty with the good. Battiato here reaches a perfect balance between classicism and avant-garde: in his own words, he’s like the “experienced sailor who has been sailing for years, learning everything from the sea”, who is very different from “the one who works for the Harbour Master’s Office and whose predictions are often wrong due to a lack of knowledge of the sea”.

His version of classical contemporary is based on a few, essential elements, interpreted by his peculiar sensibility and a very Italian sense of melody. His intimate chamber pieces, especially ‘Cafè-Table-Musik’, are simple, but never ordinary: his balera instinct allowed him to experiment without ever losing sight of a timeless sense of harmony, so much so that even after 40 years this record hasn’t aged a bit. His contribution to classical music might not have been as grand as the giants he was standing on the shoulders of, but it’s definitely up there with them.

- “The musical development of Sinfonia is constantly and strongly conditioned by the search for balance, even identity between voices and instruments; between the spoken or the sung word and the sound structure as a whole. This is why the perception and intelligibility of the text are never taken as read, but on the contrary are integrally related to the composition. Thus, the various degrees of intelligibility of the text, along with the hearer’s experience of almost failing to understand, must be seen as essential to the very nature of the musical process”. Luciano Berio, liner notes of his 1986 Erato LP. ↩︎

- “Berio was a very likeable person, frank and moody. I met him when I was twenty-five through [pianist] Bruno Canino in Milan, but as a composer he was inconclusive, he had no talent. My opinion hasn’t changed over time. I have always made a big distinction between Stockhausen and Berio, Ligeti and Boulez. I distinguish between those who do it in function of their official role [d’ufficio in the original] and those who are true composers”. Franco Battiato, quoted in Stefano Pio’s Franco Battiato & Giusto Pio. Uno sguardo dal ponte [A View from the Bridge]. ↩︎