Virtually unknown outside of Italy and a small circle of avant-garde aficionados, violinist and composer Giusto Pio revolutionised Italian pop together with Franco Battiato and wrote beautiful pages of experimental music in his solo works, from his essential take on minimalism with Motore Immobile to his late incursions in ambient and devotional music.

Giusto was a great artisan of sound who forged a very recognisable style, an artsy pop rich in classical influences where his violin was in the spotlight. Focusing on his best records, I will highlight the main features of his music and give a brief account of his biography.

The early years: Castelfranco Veneto and the war

Born in 1926 in the small town of Castelfranco Veneto, northwest of Venice, Giusto Pio started playing the violin at the age of ten. In 1941, a year after Fascist Italy joined World War II on Hitler’s side, he enrolled at the Conservatory of Venice. Luigi Nono, who would soon become a leading figure of the post-war European avant-garde, was one of his classmates, as Pio recalled in his biography Dedicato A Giusto Pio [Dedicated to Giusto Pio, 2010]: “While we stuck to the teaching programs, he ranged in every direction and was always one step ahead. Even back then, he was truly avant-garde”.

During the German occupation of Italy in 1943, the musician had to temporarily halt his studies and instead aided the partisans in their fight against the Nazis. Somehow, music played a role even in this act of resistance, with Pio hiding weapons inside his parents’ piano. Italy was liberated from the invading forces by May 1945 and the end of the war marked the start of Giusto’s career. In 1947, he completed his music studies and soon after secured a position with the national symphony radio orchestra RAI in Milan, where he relocated in the early 1950s.

The Milan years and the collaboration with Battiato

In full economic and cultural boom, Milan proved to be a turning point for Pio’s career. Home of the biggest majors, the city offered him the opportunity to work as a studio session musician for many established pop and rock acts ranging from Italian chanson to early rock. At the same time, he stared delving into ancient music, treasure-hunting obscure pieces of medieval and baroque compositions to play in small ensembles with friends and colleagues.

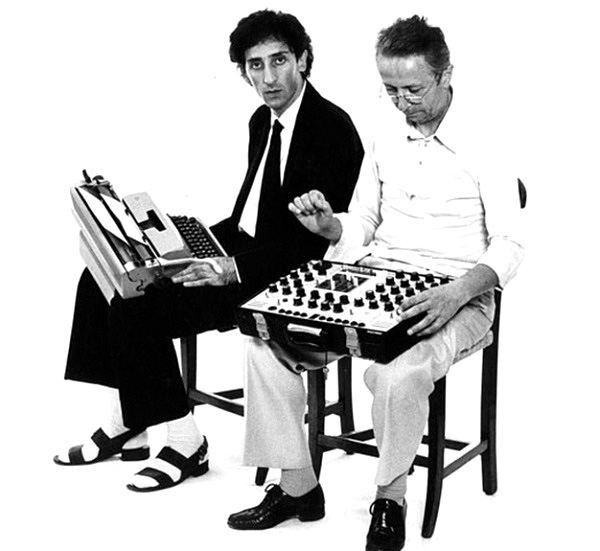

All these experiences are key to understand Giusto Pio’s musical path and what will become his signature blend of pop, classical melodies and avant-garde sounds. What truly changed the course of his career, however, was his encounter with Franco Battiato in the late 70s.

Far from his later mainstream success, Battiato was then an underground artist experimenting with prog-rock and avant-garde music. Looking for a violin teacher, in 1977 he was referred to Giusto Pio. Reluctant at first, Pio started giving him private lessons every Sunday and ended up co-writing and arranging most of his records until the early 90s. Together, they pioneered a unique avant-pop genre that reshaped the landscape of Italian popular music, selling millions of records across Italy and Europe.

1979 was a pivotal year for the duo: Giusto co-wrote and handled the arrangements of Battiato’s L’Era Del Cinghiale Bianco [The Age Of The White Boar], their first successful venture into pop, while Franco produced Pio’s first solo album, Motore Immobile, one of the great masterpieces of Italian minimalism. These records showcase the vastness of their musical horizon and their ability to move seamlessly between pop, classical and experimental languages.

Before diving into Motore Immobile, I will focus on Giusto Pio’s pop records. I’ll highlight what I consider his best albums, each representing a distinct musical style: Restoration for pop, Motore Immobile for minimalism, and “Alla Corte di Nefertiti” for ambient.

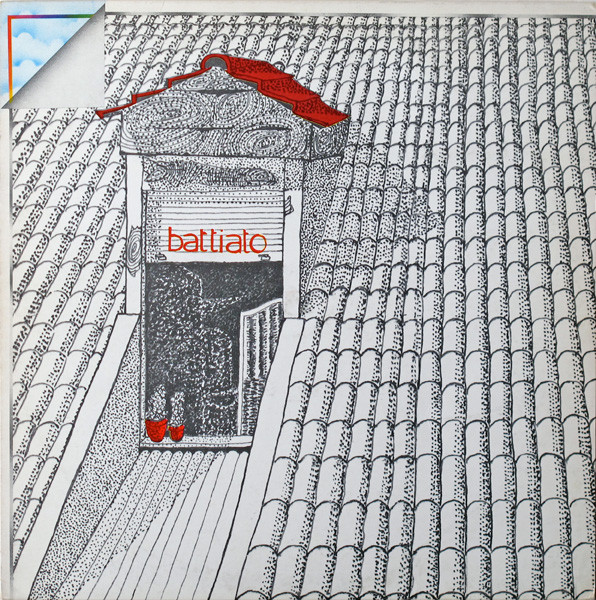

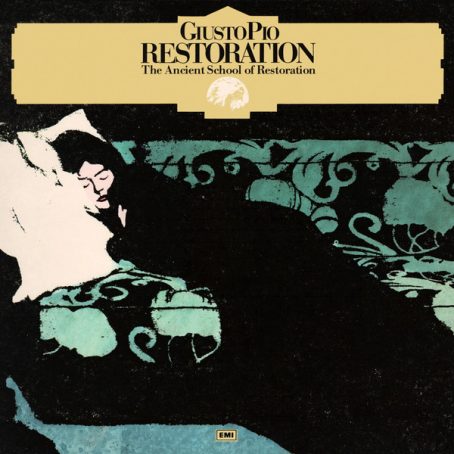

Restoration – The Ancient School of Restoration

In Milan, I used to go to antique dealers and restorers. I knew them all and visited them often: I never missed the Sant’Ambrogio fair and the street markets.

Giusto Pio, “Dedicato A Giusto Pio”

Giusto Pio’s artisanal inclination is shown at his finest in his third LP, Restoration an upbeat, violin-heavy instrumental record co-written with Battiato. It’s 1983 and Pio, at the age of 57, is at the height of his career: Together with Battiato the “grandpa of pop”, as the press jokingly called him, was touring extensively and composing countless hits for the greatest Italian pop stars of the time, to name just a few: Giuni Russo, Milva and Alice, who would win the Sanremo Festival in 1981 with a song by Battiato/Pio, Per Elisa.

The crystal clear voice of his violin is shaping a new form of avant-pop of which Restoration is the most mature example. When asked to explain the album’s title, the musician claimed that “maybe it’s time to recycle a lot of values and ideas from the past”. But Restoration couldn’t be further from the nostalgic pastiche of a man who loved to rummage through restorers’ workshops. On the contrary, the LP shines as a fresh and unique synthesis of classical references reminiscent of Baroque music, cheerful melodies, Middle Eastern harmonies and nods to New Wave – especially in the drumming which, actually, is the element that sounds the most dated.

There’s a profound joy emanating from the compositions, something akin to the sense of liberation of a skilled musician who, for the first time, experiences the freedom of expressing himself fully.

The amazing opener “Gente a lavoro” feels like a modern capriccio, fast-paced and playful, “Happy morning” bridges Eastern and Western melodies while “Rodolfo Valentino” and “Passato e Presente” display the duo’s talent for composing catchy, timeless song.

The closing track best exemplifies the process of recycling ideas from the past which Pio alluded to while explaining the album’s title. The piece “Restoration” is a reworking of French composer Gabriel Faurè’s Pavane No. 50: Giusto Pio borrows the main melodic line and rearranges it in his trademark style, transforming a classical sonata from 1887 into a radiant pop song.

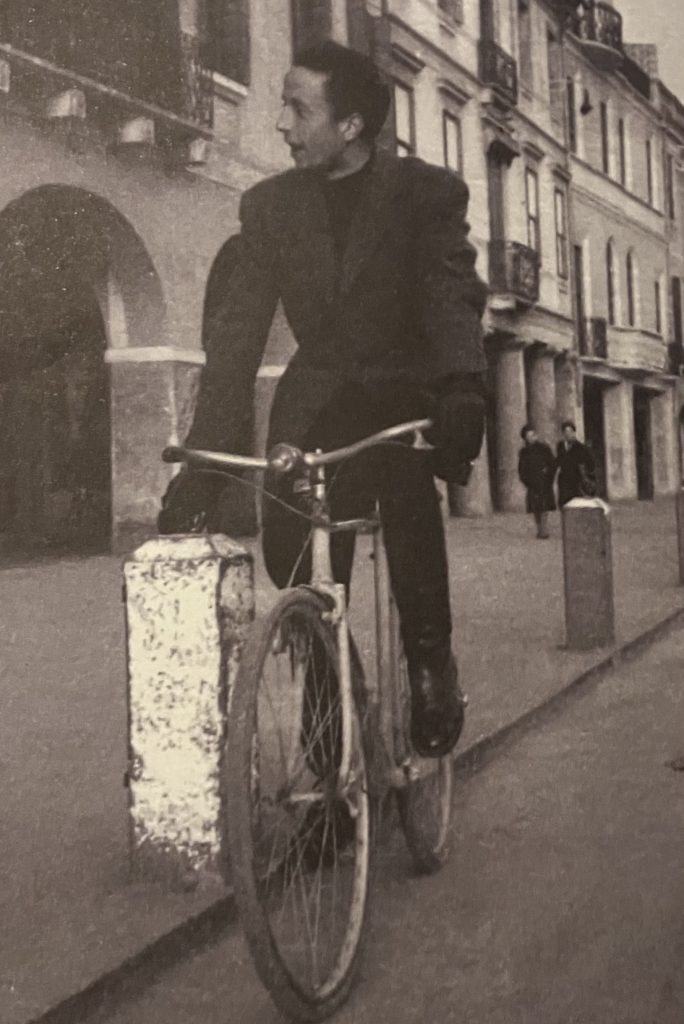

In the book Dedicato a Giusto Pio there’s an old photo of the musician riding a bicycle after the end of the war that, for me, perfectly captures the atmosphere of the record: the unbridled joy of the new beginnings reverberating through the sound of his violin.

Motore Immobile: a Minimalist Masterpiece

In 1979, as Giusto Pio was starting his pop exploration, Cramps Record released his first solo album, Motore Immobile [The Motionless Mover]. The title hints at Aristotle’s concept of the prime mover, an unchanging being responsible for all the motion and the consequent orderliness in the sensible world. In fact, the compositions of Motore Immobile sound like the still center of an ascendant movement, essential and devoid of any ornament. As exuberant and joyful is Pio’s pop writing, as intimate and ascetic is his venture into minimalistic territories.

The record comprises two extended compositions, Motore Immobile and Ananta, based on sustained triads (groups of 3 notes) played on the organ and accompanied by sparse melodic interludes from violin, piano and humming. The pieces are extremely simple and yet transcend their simplicity to embrace a higher spiritual quality. As Giusto Pio recounts:

I played around with piano pedals, trying to make the notes resonate, because sometimes – sympathetically – the notes merge into something majestic, something that transcends mere sound and enters the realm of spirituality. Franco [Battiato] brought me a series of keyboards on which I wrote long, slow chords, layered on top of each other.

Battiato contributed vocals under the pseudonym of Martin Kleist, punctuating the organ notes of the title track with his delicate humming. Echoes of his music reverberates in Ananta, whose piano chords draw on L’Egitto Prima Delle Sabbie, a piano work that earned Battiato the Stockhausen composition prize in 1978.

Motore Immobile can be clearly ascribed to minimalism, even though the pure bareness of his sound and its essential simplicity are somehow reminiscent of Arvo Pärt. Here, however, the vastness of the Estonian forest is replaced by the stillness of a monastery in the Italian countryside. The ascending tension of the music is paired with a gentle and cosy atmosphere that soothes the listener.

As spiritual as it is, in fact, there’s also a certain warmth to the sound of the album- an affectionate longing, perhaps the echo of a childhood memory. Pio recalled that “[as a young boy] I used to play the organ in the church of the neighbouring village, where I was paid with sacks of flour and a few eggs”. That memory, with its blend of affection and transcendence, certainly feels very close to the listening experience of Motore Immobile.

Sunset Boulevard: Alla Corte di Nefertiti

After 35 years in Milan and a decade of intense collaboration with Battiato, Pio returned to his hometown of Castelfranco Veneto in 1988. Feeling too old for the big city, he expressed the desire to reconnect to his roots and revisit “the sonic research behind Motore Immobile in a less stylised and condensed form”. Marking his return to experimentation after a string of pop records, the LP Alla corte di Nefertiti [In the court of Nefertiti] came out that same year. Battiato wasn’t directly involved in the composition process this time, but he released the album on his own imprint, L’Ottava, which he had set up primarily to publish Gurdjieff’s writings in Italian translation.

The Armenian mystic had a significant influence on both Battiato and Pio: in the 1980s the two attended the Milan group meetings of Henri Thomasson, the scholar who introduced Gurdjieff’s teachings to Italy. Giusto Pio maintained that his later experimental music was inspired by the “strong, deep suggestions and emotions felt during those meetings, where I was trying to look inside myself”.

Giusto composed the two extended pieces of Alla Corte di Nefertiti in the solitude of his home studio. For the first time, the electronics take center stage, creating delicate soundscapes reminiscent of Harold Budd: the pace is slower, perhaps reflecting Pio’s new environment, and the atmosphere is more introspective, veering into ambient and meditative music. The record was written as a soundtrack for an obscure sculpture exhibition, as reflected in the attention to tone colours and the tactile quality of the notes, akin to a canvas of sound. It’s no accident that Giusto Pio was also a visual artist: he began painting abstract works as a young man and described music and painting “not only contiguous and similar but also somehow identical, interchangeable in the sense that I feel music as form and color”.

The title-track of Nefertiti ends with a hushed synthetic choir, hinting at the sacred music Giusto Pio would devote himself to in his final years, resorting to electronics instead of real musicians due to a lack of interest and support from labels and the music business at large. Starting from Alla Corte di Nefertiti his music is enshrouded in a certain melancholy, perhaps a meditation on the old age: never dark or oppressive, it’s rather autumnal, gently expressing the nuances and impressions of a new season of life.

Asked about his feelings about the old age in one of his last interviews in 2012, Giusto replied:

You feel that what was once essential is no longer indispensable. But it’s not a renunciation, it’s natural. I have no nostalgia for the past. Through my music, I have tried to go as deep as possible to explore those unknown worlds. In one of my compositions, where life ends, there is a beam of sounds that is like a light, and it goes on and on for more than a minute: two, three notes together that get lost in infinity.

Giusto Pio died in 2017 at the age of 91 in Castelfranco Veneto.

Grazie per la musica, Maestro.